Today the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the ongoing detention of Osman Kavala, philanthropist, human rights defender and a defendant in the ‘Gezi Park Case’, violates his right to liberty and security of the person (see here). In a landmark finding, the European Court further declared that his detention pursued an ulterior purpose, only the second such finding against Turkey under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The proceedings against Mr Kavala relate to the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Istanbul, when an initial protest against the ‘development’ of the Gezi Park green-space grew into a mass nationwide protest against the AKP government (for a review of Turkish policing on the protests, see here). Mr Kavala was charged, along with 15 others, of organising and leading the Gezi protests in an attempt to overthrow the constitutional order and the Government. Together with Mücella Yapıcı (Board Member of the Istanbul Chamber of Architects) and Yiğit Aksakoğlu (Turkey Representative of the Bernard van Leer Foundation), he faces life imprisonment.

The basic facts of Mr Kavala’s detention and the prosecution documents expose a politicised prosecutorial system. Mr Kavala was arrested four years after the Gezi Park protests, held without charge for a period of 16 months, and charged five and a half years after the events in question. Running to 657 pages, the indictment presented a series of general references to protest movements outside of Turkey and claims Open Society Foundations founder George Soros funded the Gezi protests. The indictment did not indicate any actual examples of law breaking by Mr Kavala. What it did demonstrate was the extent of physical and electronic surveillance conducted by the Turkish authorities, referring repeatedly to directly observed meetings and listing transcripts of telephone calls made and received by the defendants.

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, attested before the Court to Mr Kavala’s long record of engagement as a partner to various Council of Europe and European agencies and representatives (see here). Given his reputation and distinguished record of human rights work, Mr Kavala’s detention has had a distinct chilling effect on civil society. It is one part reprisal, one part silencing, and one part warning.

Arbitrary Detention and the Constitutional Court as an Effective Remedy

The European Court’s findings flow from one simple observation: a lack of evidence that Mr Kavala had committed any criminal acts. In the Court’s view, there was no basis for a reasonable suspicion against Mr Kavala at the time of his detention. There were no “facts, information or evidence showing he had been involved in criminal activity”. Nor had any of the evidence presented following his arrest given rise to a suspicion justifying his continued detention. The Court found both his initial detention and its continuation were in violation of his human rights and commented:

“…the prosecution documents refer to multiple and completely lawful acts that were related to the exercise of a Convention right and were carried out in cooperation with Council of Europe bodies or international institutions (…). They also refer to ordinary and legitimate activities on the part of a human rights defender and the leader of an NGO, such as conducting a campaign to prohibit the sale of tear gas to Turkey or supporting individual applications.”

The Court also gave a landmark finding on the Turkish Constitutional Court: the almost seventeen-month delay in deciding on the lawfulness of Mr Kavala’s detention was excessively long and in violation of his rights (Article 5 (4) ECHR), the first such finding against the Constitutional Court.

The Court has previously accepted that the situation following the attempted coup d’état of 15 July 2016 presented an exceptional challenge to the workload of the Constitutional Court. On that basis it accepted the Constitutional Court might take longer to take decisions (see here), and ruled that a delay of 1 year and 16 days was not speedy but nonetheless did not violate Article 5 (4) ECHR (see here). In the case of Mr Kavala, however, the Court’s patience has come to an end. It stressed the “primordial role” of the Constitutional Court in guaranteeing detainees’ rights, particularly given the recognised dissuasive effect on Mr Kavala’s detention, and closed the door on excuses: “the excessive workload of the Constitutional Court cannot be used as perpetual justification for excessively long procedures”.

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, noted before the Court (see here) that the Constitutional Court had given a mere 104 judgments finding violations of liberty and security of the person between September 2012 and December 2018, despite receiving almost 16,000 such claims in the same period. In her view, there was sufficient evidence to cast doubt on the effectiveness of the Constitutional Court’s individual application procedure. The Court’s decision did not go that far, but its finding that the Constitutional Court had violated Mr Kavala’s rights is a long overdue and essential decision on detainees’ rights. The Constitutional Court’s status as an effective domestic remedy, as a rule, is no longer sustainable.

Restrictions on Rights

The Court’s decision on whether Mr Kavala’s detention was a restriction on rights, contrary to Article 18 ECHR, is another indication of the severity of the situation in Turkey. Article 18 remained in obscurity until quite recently (for comment, see here) and a violation was upheld for the first time against Turkey in November 2018, in the case of former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş. But Article 18 violations are by no means commonplace at Strasbourg and the fact of two such findings against Turkey in 13 months, while it remains under special monitoring by the Council of Europe (see here), speaks to a significant problem beyond mere ‘democratic backsliding’.

Article 18 requires evidence that a specific action served an ulterior purpose, i.e. one not permitted under the ECHR, and that must have been the “predominant purpose” of the impugned action. On the issue of whether Mr Kavala’s detention served an ulterior purpose, the Court referred to a broad campaign in Turkey within which his arbitrary detention is to be understood. The indictment against him was also internally inconsistent – why would the Turkish authorities allow a man capable of, and allegedly having committed, such serious offences to remain free for so long? The timing of the indictment against Mr Kavala was, in fact, a sign of something more troubling. As recognised explicitly by the European Court, he was indicted soon after President Erdoğan had publicly denounced him as the “national pillar” behind the Gezi Park protests. The Court concluded:

“The Court considers it to have been established beyond reasonable doubt that the measures complained of in the present case pursued an ulterior purpose, contrary to Article 18 of the Convention, namely that of reducing the applicant to silence. Further, in view of the charges that were brought against the applicant, it considers that the contested measures were likely to have a dissuasive effect on the work of human-rights defenders.”

The Court’s judgment provides a crucial update to the monitoring of human rights in Turkey, confirming an ongoing erosion of the rule of law. Through its Article 18 finding, in particular, the Court has provided an unequivocal statement on the precarious situation of civil society actors and human rights defenders in Turkey.

Conclusion

Today’s judgment adds to the already significant evidence of systemic human rights violations in Turkey. It also indicates that the European Court has awoken to and recognised the reality of political persecution in Turkey: of arbitrariness, of targeting, and of criminalisation of legitimate political activity. The finding that the Constitutional Court failed to guarantee Mr Kavala’s rights speaks to bigger problems with the administration of justice and domestic protection of human rights in Turkey. The Court’s call for the immediate release of Mr Kavala must be backed-up urgently, and without retreat, by all Council of Europe and United Nations human rights representatives.

DARREN DINSMORE

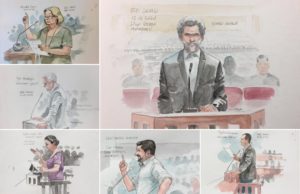

Images Sources :

1- Gezi Park Protests (VikiPicture / CC BY-SA) https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/07/2013_Taksim_Gezi_Park_protests%2C_Protests_at_Gezi_Park_on_3rd_June_2013.JPG

2- Murat Başol, Bianet : https://m.bianet.org/bianet/ifade-ozgurlugu/220240-gezi-davasi-kronolojisi