“Those who opposed (the project) were accused of being political. Even if you’re an environmentalist, a patriot, or animal lover, they labelled you as something else when you said ‘Stop!’ to the project. Now, we’re watching history slowly disappear” (see here

From the Bamiyan statues (see here) to the cities of Palmyra (see here) and Nimrud (see here), and many others in between, recent experience emphasises the enduring symbolic power of sites of cultural heritage, transcending national borders and capturing imaginations. The widespread global reporting on the destruction of Palmyra in Syria by Da’esh through 2015 and 2016 routinely portrayed the destruction as evidence of barbarity, of inhumanity. Palmyra and Nimrud appeared in this sense as recent, tragic high points in awareness of the vulnerability of sites of universal value.

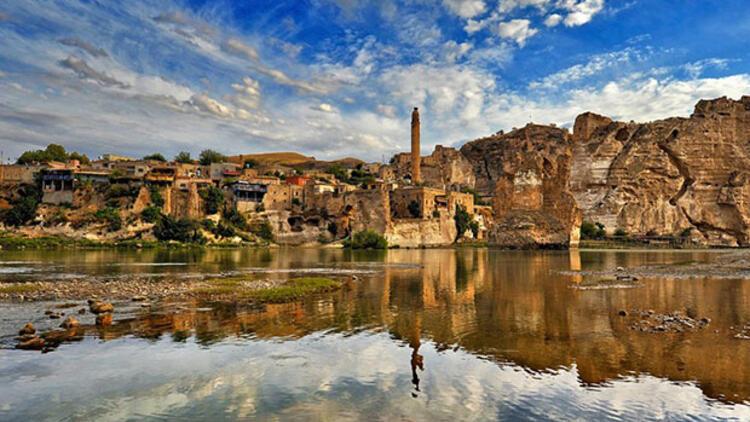

Of course, acts of “cultural cleansing”, as UNESCO condemned the destruction of Palmyra (see here), are certainly not exclusive to Dae’sh and other extremist groups. Nor are sites of cultural heritage threatened only by war or conflict. A large proportion of World Heritage sites remain threatened by fossil fuel extraction and other industrial activities (see here) and sites not officially recognised as of ‘Outstanding Universal Value’ (see here) see little formal protection under international law in the face of development projects. The current flooding of the 12,000 year-old city of Hasankeyf in Bakur / South-east Turkey, a city that has been home to more than 20 cultures, exposes protection gaps in international law and represents a further landmark in irreplaceable cultural loss.

The Southeastern Anatolia Project and the Ilısu Dam

Built on the banks of the River Tigris, the city of Hasankeyf is being flooded as part of the world’s largest dam project under construction, the Ilısu dam. The 1,200 MW and $2 billion Ilısu dam project sits around 60km from Turkey’s borders with Iraq and Syria and affects a large swathe of the Kurdish region (including the provinces of Batman, Diyarbakır, Mardin, Siirt and Şırnak). Since the mid-1950s successive Turkish governments have planned works under the ‘South-eastern Anatolia Project’ (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, GAP; see here) in predominantly Kurdish areas, involving the construction of 22 large dams, 19 hydroelectric power plants and 12 irrigation and hydropower schemes on the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers.

In Hasankeyf, a city of Kurdish and Arabic inhabitants, the reservoir began filling in July 2019 and people have been compelled to move to the new city of ‘New Hasankeyf’ (Yeni Hasankeyf) or to regional urban centres. A further 199 villages are in the firing line, meaning the dam will displace between 55,000 and 80,000 people and affect a further 20,000 nomadic people. Rising waters daily are also seeing the loss of hundreds of archaeological sites, the majority of which have not been surveyed or excavated, including man-made caves dating back to the Neolithic era and the historic Hasankeyf fortress. Some artefacts have been removed and placed in a new museum, while the 600 year-old Zeynel Bey Tomb, a powerful regional symbol (see here), has been moved to higher ground. The dam will also have a severe environmental impact, causing irreparable harm to unique ecosystems and habitats, and affecting the water supply to Iraq and Syria (see here).

The Atlantic has published a series of 29 photographs of the affected area and cultural sites prior to flooding (see here). The NASA Earth Observatory provides the most recent images of the current state of flooding (see here).

Turkey has shown repeated determination to proceed with the Ilısu dam project whatever the costs, harm caused or legal hurdles. Financing was found despite a lack of initial investors in 1996, only to be lost in 2002 due to a lack of environmental due diligence. In 2009, European Export Credit Agencies withdrew guarantees totalling $450 million due to lack of progress on environmental, social and cultural heritage commitments, leading the Turkish government to proceed with national private and public loans. When an administrative court stopped the project in 2013 due to the lack of an Environmental Impact Assessment (see here), the government simply amended the law to allow the project to continue. Of course, Turkey had long refused to apply for UNESCO status for Hasankeyf in spite of claims it met 9 out of 10 criteria (see here).

Turkey’s uncompromising approach is explained by its de facto state ideology, as a result of which Kurds have been systematically denied constitutional recognition and political freedom. Turkish security forces perpetrated a violent pattern of forced displacement during conflict with the PKK (Kurdistan Worker’s Party) in the 1990s (see here), mirroring past policies of forced movement of Kurdish populations. The GAP project ties into a more publicly presentable narrative that solutions to the 40-year war with the PKK (Kurdistan Worker’s Army) depend on socio-economic development rather than human rights and cultural freedom for Kurds. In the process, the Ilısu dam project demonstrates the Turkish State’s blatant disregard for the regional historical and cultural record.

International Law: Cultural Heritage and Displacement

The Ilısu dam project engages various areas of international law, including standards on cultural heritage, forced displacement, forced eviction and resettlement. The potential problems with dam projects are well known: inadequate consultation, lack of consideration of alternatives, lack of sufficient compensation, inadequate provision or quality of alternative housing, lack of provision of health services and community support, and disproportionate effects on women, among others. The Ilısu dam project continues to expose the limitations of international legal mechanisms and institutions in securing respect for standards on development-induced displacement and resettlement. As observed by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (see here), the Turkish Government has failed to conform to basic norms:

“[D]evelopment should be equitable and inclusive but to date the resettlement process associated with the Ilısu project has run counter to this ethos”

The Turkish authorities have refused to consult and provide accurate up-to-date information throughout; as just one example, a 2005 resettlement plan was initially published in English and shared only with the Export Credit Agencies. Proposed schemes to assist the people displaced/evicted by the dam have been plainly insufficient – from a lack of resettlement sites suitable for agriculture to the decision to limit expropriation payments to registered properties – and do not satisfy the World Bank rules or the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on Development-Based Evictions and Displacement.

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has developed standards on forced evictions and development-induced displacement (see here) which set out a series of duties on States regarding consultation, consideration of alternatives and compensation. Turkey has not signed or ratified the Additional Protocol that allows the Committee to receive complaints, meaning the only option regarding Ilısu lay with the ‘State Reporting procedure’ (see here), a procedure ill-equipped to handle problems of this nature.

In July 2011, following a submission by the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive and others (see here), the UN Committee issued ‘Concluding Observations’ on Turkey’s State Report. The Committee stated that it was “deeply concerned” at the potential impact of the Ilısu dam and Turkish compliance with legal standards regarding forced eviction, resettlement, displacement and compensation, as well as the environmental and cultural impact (see here). It called on the Government to “undertake a complete review of its legislation and regulations on evictions, resettlement and compensation.” The response has seen little improvement. The UN human rights system offered no realistic prospect of stopping the Ilısu dam project through socio-economic rights claims.

Further efforts to use international human rights law involved legal action under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), through its civil and political rights provisions. A creative but unsuccessful complaint to the European Court of Human Rights exposed a significant protection gap regarding the protection of cultural heritage through human rights law. In its January 2019 decision to dismiss the application, as inadmissible (see here) the European Court commented:

“The Court is ready to consider that there is a European and international view on the need to protect the right of access to the cultural heritage. However, (…) in the current state of international law, the rights linked to cultural heritage seem intrinsic to the specific statuses of individuals who benefit, in other words, from the exercise of the rights of minorities and indigenous peoples.”

Under international law, therefore, there is currently no direct legal interest in and right to cultural heritage outside the sphere of minority or indigenous rights (see in connection: here). While this decision blocked the use of the European Convention on Human Rights as a tool to stop the Ilısu dam project, it also clearly indicates the possibility for future developments in human rights law. It implies that a claim regarding the destruction of sites of historical or cultural significance to Kurds could potentially succeed, although the legal hurdles involved are not to be under-estimated. Further ECHR claims relating to compensation and property rights are still possible for those affected by the Ilısu dam. In the meantime, with domestic and international legal options exhausted, we watch history slowly disappear.

DARREN DINSMORE

Image source: https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/kelebek/8-maddede-hasankeyf-in-insanlik-tarihi-acisindan-onemi-29472556