The current crisis of international law is often described as an “increase in violations.” Yet the problem is not only the breach of norms. The more structural problem is that the language of norms and rights is increasingly taking an active role in rendering cross-border coercion governable and capable of being legitimised. For this reason, modes of “governing from within the law” are as decisive as “stepping outside the law.” What is at stake here is not the suspension of law, but law becoming the central language of crisis management. Put differently, today’s crisis of international law is not a lack of norms; it is a structural “outcome-production” crisis that emerges because the enforcement of norms has been tied to political filters. Legal texts, prohibitions, and definitions of crimes remain in place; yet the responsibilities that follow from these norms, especially where the use of force is concerned, are not triggered equally and necessarily. They are activated selectively depending on context, actor, and political cost.

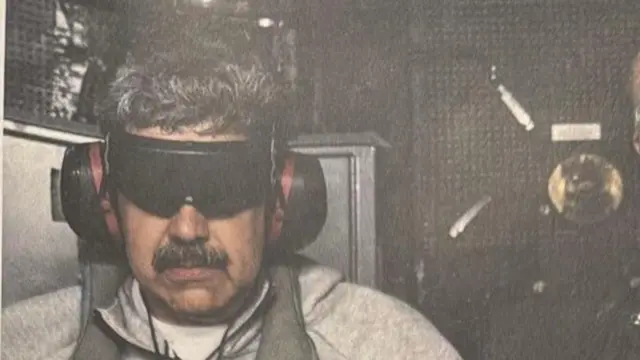

This article analyses the threshold international law has reached through the case in which, on 3 January 2026, U.S. forces in Venezuela “captured and removed from the country” President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, and the United States justified this both through a criminal investigation and through a discourse of political “control.”

Reuters reports that the operation was carried out through large-scale use of military force, that Maduro was taken to the United States, and that U.S. President Donald Trump said the United States would “control” Venezuela until the country entered a “safe transition.” This framing requires attention not only to the military or criminal dimensions of the intervention, but also to how it is constructed legally and discursively. The case makes visible a regime in which jus ad bellum and penal discourse can be blended; in which interstate military force can be presented as a police–criminal “law enforcement” activity conducted in a foreign country; and in which sovereignty and domestic law-enforcement claims can be merged on the same discursive plane.

Within this framework, three questions are decisive. First, if the prohibition on the use of force and the idea of the crime of aggression exist normatively, why do such cross-border operations remain “doable”? Second, under what conditions do rights- and punishment-centred discourses, instead of strengthening the criminalisation of war, depoliticise it and turn it into a technique of governance? Third, how do ambiguities of representation and consent lower the legal cost of international law and erode accountability?

What happened?

According to media reports, the United States captured Maduro through a military operation carried out in Caracas; it conducted months of covert preparation beforehand, and it used large-scale air strikes and special forces elements simultaneously. [1] Reuters also notes, in a report drawing on legal assessments from different experts, that the U.S. administration presented the operation as a “law enforcement” activity while simultaneously making statements aimed at establishing political control over Venezuela, and that experts found this dual justification inconsistent in terms of legal technique.

In this case, the “event” is not the capture alone. The event is the legal regime into which the capture is placed. The U.S. narrative is built along two tracks. The first is an individual criminal responsibility track, framed through federal indictments and “narco-terror” allegations. The second is a track of actual military force and political control. The tension Reuters points to emerges precisely here: a state uses military force on another state’s territory to detain its leader, and then seeks to normalise this through the language of “criminal justice” and “public order.”1

This dual framing concretises the thesis that law has become the language of crisis management. In this context, law functions less as a threshold that constrains the use of force than as a repertoire that converts the use of force into a governable procedure. The core function of this repertoire is not to render the violation invisible; it is to remove the violation from the register of extraordinary rupture and place it within an administrative logic of “transition.”

Jus ad bellum: Sovereignty, and the prohibition of intervention

Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibits states from using force and from threatening to use force[2]. This prohibition can be overridden only through Security Council authorisation or self-defence. Self-defence, under Article 51 of the UN Charter, depends on the condition of an armed attack and on the criteria of necessity and proportionality[3]. In this case, no framework appears to exist in terms of Security Council authorisation or Venezuela’s explicit consent.

The U.S. “law enforcement” claim does not produce a persuasive legal basis at the level of jus ad bellum. In international law, cross-border “arrest” and “capture” can be discussed only with the host state’s consent, or—very exceptionally—under conditions that do not cross the thresholds of the use of force. Here, however, the scale reported is not a “police operation” but a state’s exercise of military force in another state’s capital.1 For this reason, the claim of a breach of the prohibition on the use of force is not merely a political critique; it concerns the core of jus ad bellum.

At this point, “sovereignty” is not merely a symbolic principle. Sovereignty is a foundational legal arrangement concerning which authority holds the monopoly of violence on its own territory. As the International Court of Justice stated in the Nicaragua case, the forcible detention of a person on another state’s territory constitutes a breach of the prohibition of intervention and of sovereignty[4]. This breach produces a shift not only in interstate relations but also in the constituent logic of the international order. For such an act deliberately blurs the lines between “sanction” and “war,” and between “punishment” and “intervention.”

Where law becomes the language not of drawing lines but of stretching them, war ceases to be an exception and becomes institutionalised as a technique of governance. In the Maduro case, the central issue is not the existence of the violation; it is how the violation is recoded through the language of “law enforcement” and “crisis management.”

International crime regimes and the marginalisation of jus ad bellum

The crime of aggression is defined in the Rome Statute[5]. The distinctive feature of the crime of aggression is that it places at the centre of criminal responsibility not how war is waged, but the decision to wage war itself [6]. At Nuremberg, a war of aggression was described as the “supreme international crime.” [7]

The critical consequence today is this: while many crises are discussed at the level of civilian harms and war crimes, the unlawfulness of the resort to force is systematically pushed into the background. In this context, Cassese’s emphasis that aggression remains “one of the most serious gaps” regains its importance. [8]

A similar risk exists in the Maduro case. Framing the debate around “narco-terror” and individual criminal allegations renders the unlawfulness of the cross-border use of military force invisible. Yet allegations of organised crime or narcotics do not, from the standpoint of jus ad bellum, constitute a justification for the use of military force. The fundamental question is how to characterise, under the prohibition on the use of force, a state’s capture of a foreign head of state through a military operation.

Here, a structural blockage becomes visible. The justiciability of the crime of aggression in the International Criminal Court regime is tied to political thresholds. Although the Rome Statute defines the crime of aggression, the Court’s jurisdiction over that crime depends to a large extent on a Security Council determination or on states’ consent[9]. This turns aggression into a category that is normatively recognised yet practically unenforceable.

Accordingly, the problem is not the absence of norms but the selective political application of norms. This selectivity preserves cross-border uses of force as a policy instrument that is legally prohibited yet practically available.

Jurisdiction over a head of state: combining penal discourse with a breach of sovereignty

The immunity of sitting heads of state from the criminal jurisdiction of foreign states is a deep-rooted part of customary international law. This immunity exists not to “exonerate the person,” but to restrain the use of force in interstate relations. The forcible capture of a head of state while in office, and their insertion into another state’s criminal system, is not only a “trial” issue; it is an erosion of one of the international order’s conflict-preventive mechanisms. The ICJ’s Arrest Warrant judgment is a key reference that clarifies the rationale of immunity[10].

In the Maduro case, the U.S. penal narrative does two things at once. On the one hand, it criminalises political leadership under the guise of “fighting crime.” On the other hand, it uses this criminalisation to legitimise military action on sovereign territory. This is the moment at which criminal law becomes not a boundary-setting device, but the “language” of cross-border coercion.

The issue is not only that international criminal justice does not function. The deeper, more structural issue is that the language of law and rights is no longer operating as a normative framework that constrains political and social crises; it is becoming the primary language and technique that renders these crises governable. In other words, law is not being suspended; it is, on the contrary, being activated intensively with a new function.

This also shows how, in the neoliberal period, rights discourse has been detached from the historical context of social struggle to which it was once tied, becoming a technology of governance aimed less at transforming unequal power relations than at administering them[11]. In this context, arguments about punishment, human rights, and the rule of law do not function as boundaries that stop the use of force; rather, they frame it as a “justifiable” and “rational” form of intervention.

This shift has long been debated in critical international law literature. As Koskenniemi emphasises, the flexible and indeterminate structure of international law enables legal arguments to reproduce political preferences under the language of neutrality[12]. Orford’s analyses of humanitarian intervention and protection discourse show that, in moments of crisis, law can shift from a limiting function to a guiding and legitimating one[13]. Within this framework, penal discourse becomes an intermediate language that replaces debate about the unlawfulness of force and presents military action as a governance intervention.

At this point, the function of the “rule of law” argument becomes critical. If law normalises cross-border action carried out at the price of violating sovereignty in the name of a “greater justice,” the international legal order ceases to be a braking mechanism. The language of “prosecution” thus turns into a technique of governance that substitutes for the language of “intervention.”

The consent doctrine, the problem of representation, and sovereignty gaps

The consent doctrine is a commonly used tool for legitimising foreign military presence. Yet in civil wars, transition regimes, and conditions of fragmented sovereignty, the question “who can consent” becomes decisive. As Deeks shows in her discussion of “consent in civil war,” this produces grey zones in international law[14]. This grey zone does not remove the prohibition on intervention, but it risks reducing the legal debate from a “threshold of legitimacy” to a “procedural detail.”

In the Maduro case, there is visibly no claim of consent. Yet it is precisely this absence that activates representation and sovereignty debates in another form. Trump states that the United States will “control” Venezuela until a “transition.” [15] Such a statement is not merely about “capture”; it is an imagination of de facto governance. And an imagination of de facto governance approaches the most sensitive threshold of international law: forcible regime change and the law of occupation.

The language of “managing the transition” reflects a tendency to suspend a country’s political representation and to turn sovereignty into a temporary object of governance. The UN Secretary-General’s warning of a “dangerous precedent” shows how this tendency is perceived in terms of the international order[16]. The representation gap here operates not as a legal act producing consent, but as a de facto arrangement in which consent is not sought.

For this reason, representation gaps may function not only in contexts such as Syria or other civil wars, but also in cases where states such as Venezuela—with uncontested sovereignty and international recognition—are directly targeted. Sometimes the representation gap is built not around the question “who consented,” but around the question “who can govern.” When a leader is declared “illegitimate,” the question of to whom sovereignty belongs is answered not through law but through power. Law does not draw a boundary here. Law is made into the language of crossing boundaries[17].

This point is especially important because the permanence of what is framed as “temporary” is one of the main ways in which war is normalised today. The exception ceases to be a one-off deviation and becomes institutionalised as a crisis-management technique.

Administrative control of the humanitarian sphere: reducing life to a technical variable

Another salient face of law becoming an instrument of crisis management is the transformation of the humanitarian sphere from an area of protection independent of military force into a regime of administrative and technical control. In this transformation, coercion is not only bombing or military attack; it is also the permits, registration regimes, financial restrictions, and institutional vetting mechanisms that determine the conditions under which life can be sustained.

This may not appear at the direct centre of the Maduro case. Yet the normalisation, in the political justification of the operation, of discursive packages such as “democracy,” “humanitarian crisis,” “irregular migration,” and “drug violence” operates on the same plane as the logic of administratively managing the humanitarian sphere. Law becomes a framework that both “diagnoses the crisis” and “produces authority to manage the crisis.”

The framing used when reporting that the UN Security Council would meet on Venezuela and that the UN Secretary-General issued a “dangerous precedent” warning indicates that the transformation concerns not only the use of force but the entire architecture of crisis governance. This architecture is seen clearly in the UN Secretary-General’s warnings, in the Gaza context, against the suspension of international NGOs’ operations[18]. The transfer of humanitarian assistance into a domain of permits, registration, and administrative discretion turns the sustainability of life into a matter of technical licensing. This is the concrete expression of the observation that “coercion” operates not only through bombing but also through administrative techniques capable of suspending life. Coercion is no longer only military execution; it is the ensemble of administrative decisions that render life governable.

This framework connects to the Maduro case in the following way. When a state intervenes in another state’s political sphere through the language of “punishment” and “reform,” it often makes the humanitarian sphere part of the same governance package. Orford’s observation that “humanitarian intervention” and “protection” discourses can assume a guiding rather than a constraining role retains analytical value here.

Where should the legal strategy be built?

In conclusion, it would be insufficient to treat the U.S. capture of Maduro as a singular violation of international law. This case does not point to an emergency in which law is suspended; it points to a governance regime in which law has become a central language and technical repertoire that renders cross-border coercion governable and capable of being justified. Put differently, what we face is not the absence of law, but the repurposing of law.

This mechanism, also describable as neoliberal governance fundamentalism[19], operates on two planes simultaneously, as shown above. On the one hand, war ceases to be an exceptional rupture and becomes a durable mode of governing. On the other hand, under conditions of social disintegration and institutional fatigue, violence acquires an “arbitral” capacity; legal and administrative tools, instead of constraining that violence, render it manageable. The repurposing of law produces a technical repertoire that regulates crises emerging at the intersection of these two planes.

The Maduro case makes this transformation particularly visible. The intervention is not constructed as an extra-legal rupture; it is constructed within legal language together with a criminal investigation, public-order claims, transition management, and stability discourse. This enables the violation not to be rendered invisible, but to be removed from the register of extraordinary deviation and placed within an administrative logic of “transition.” The central risk is that the normative threshold of international law is eroded through the language of “law enforcement” and “criminal justice.” When penal discourse ceases to constrain the use of force and begins to function as a technique for managing the use of force, law’s braking capacity weakens.

For this reason, legal strategy cannot be reduced to identifying the violation alone; it must be rethought across three planes at once. First, the normative threshold of jus ad bellum must be kept constantly in view against its marginalisation. Despite all problems of selective enforcement, the prohibition on the use of force and the idea of the crime of aggression remain the basic legal framework that records that cross-border coercion is not ordinary politics. Second, against the depoliticising effect of penal and rights discourse, violations must be re-situated within the power relations that make them possible. Legal analysis must not be limited to individual allegations; it must reveal how these allegations are articulated to a military and administrative execution. Third, it must be made visible how gaps of representation and sovereignty erode accountability, and how concepts such as consent, transition, and stability function as techniques of governance; these must be brought to the centre of legal debate.

What we face today is not the complete collapse of international law. More dangerous is law becoming a central tool in rendering war and coercion governable. The fundamental question, in this context, is not a call for “more law.” The real question is which legal imagination will be defended. Will law be preserved as a threshold that draws lines and records violations, or will we accept its becoming a language that manages crises and normalises exceptions?

It must also be said that law should be rethought not as a final solution, but as a field that operates within political struggles, sets limits, and makes objection possible. For this very reason, the Maduro case should be read not only as an international law file, but as a warning threshold about the place of law within today’s crisis regime.

Rüştü DEMIRKAYA

Board Member, International Mojust Foundation

PhD Candidate, University of Geneva

[1] Reuters. (2026, January 3). Was the US capture of Venezuela’s president legal?

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/was-us-capture-venezuelas-president-legal-2026-01-03/ (04.01.2026)

[2] United Nations. (1945). Charter of the United Nations (Article 2(4)). United Nations.

https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/chapter-1 (04.01.2026)

[3] United Nations. (1945). Charter of the United Nations (Article 51). United Nations.

https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/chapter-7 (04.01.2026)

[4] International Court of Justice. (1986). Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment of 27 June 1986. ICJ Reports 1986, p. 14.

https://www.icj-cij.org/case/70 (04.01.2026)

[5] International Criminal Court. (1998). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Art. 8 bis). International Criminal Court. https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/2024-05/Rome-Statute-eng.pdf (04.01.2026)

[6] United Nations. (2010, June 11). Review Conference of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: Resolution RC/Res.6 (The crime of aggression). United Nations Treaty Collection.

https://treaties.un.org/doc/source/docs/RC-Res.6-ENG.pdf (04.01.2026)

[7] International Military Tribunal. (1946). Judgement: The law relating to war crimes and crimes against peace (Nuremberg Judgement). https://crimeofaggression.info/documents/6/1946_Nuremberg_Judgement.pdf (04.01.2026)

[8] Cassese, A. (1999). The statute of the International Criminal Court: Some preliminary reflections. European Journal of International Law, 10(1), 144–171.

https://ejil.org/pdfs/10/1/570.pdf (04.01.2026)

[9] Kress, C. (2017). On the activation of ICC jurisdiction over the crime of aggression. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 16(1), 1–17. Akande, D., & Tzanakopoulos, A. (2018). The crime of aggression before the International Criminal Court: Jurisdiction and admissibility. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 16(2), 291–316. Ambos, K. (2018). The crime of aggression after Kampala. German Yearbook of International Law, 53, 463–509.

[10] International Court of Justice. (2002). Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium), Judgment of 14 February 2002. ICJ Reports 2002, p. 3. https://www.icj-cij.org/case/121 (04.01.2026)

[11] D’Souza, R. (2018). What’s wrong with rights? Social movements, law and liberal imaginations. Pluto Press.

[12] Koskenniemi, M. (2005). From apology to utopia: The structure of international legal argument (Reissue with a new epilogue). Cambridge University Press

[13] Orford, A. (2011). International authority and the responsibility to protect. Cambridge University Press.

[14] Deeks, A. S. (2012). “Unwilling or unable”: Toward a normative framework for extraterritorial self-defense. Virginia Journal of International Law, 52(3), 483–550.

[15] BBC News. (2026, January 4). Trump says US will ‘run’ Venezuela and ‘fix oil infrastructure’

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cd9enjeey3go (04.01.2026)

[16] Reuters. (2026, January 3). UN chief says Venezuela-US action sets dangerous precedent. Reuters.

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/un-chief-venezuela-us-action-sets-dangerous-precedent-2026-01-03/ (04.01.2026)

[17] Read more about this topics: Roth, B. R. (1999).Governmental illegitimacy in international law. Oxford University Press. Perišić, P. (2019).Intervention by invitation: When can consent from a host state justify foreign military intervention? Russian Law Journal, 7(4), 4–33. Green, J. A. (2024). The relationship between collective self-defence and military assistance on request. In Collective self-defence in international law (pp. 276–311). Cambridge University Press. Koskenniemi, M. (2005). From apology to utopia: The structure of international legal argument (Reissue with a new epilogue). Cambridge University Press. Orford, A. (2011). International authority and the responsibility to protect. Cambridge University Press.

[18] Reuters. (2026, January 2). UN chief deeply concerned over Israel’s suspension of NGOs. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/un-chief-deeply-concerned-over-israels-suspension-ngos-2026-01-02/ (04.01.2026)

[19] “ I use the expression “neoliberal governance fundamentalism” to describe the transformation of law into a language that normalises the exception and manages crisis rather than constraining it. This concept refers to a mode of governance in which legal norms, humanitarian rationales, and managerial techniques are mobilised not to suspend law, but to repurpose it as a permanent apparatus for administering instability, coercion, and emergency. The notion draws on the literature on the state of exception, humanitarian governance, and critical international law, which has shown how law increasingly operates as a flexible and instrumental repertoire that stabilises exceptional measures and renders crisis rule routine rather than exceptional. See more : Agamben, G. (2005). State of exception. University of Chicago Press. Kennedy, D. (2004). The dark sides of virtue: Reassessing international humanitarianism. Princeton University Press. Fassin, D. (2012). Humanitarian reason: A moral history of the present. University of California Press. Koskenniemi, M. (2005). From apology to utopia: The structure of international legal argument. Cambridge University Press. Orford, A. (2011). International authority and the responsibility to protect. Cambridge University Press. D’Souza, R. (2018). What’s wrong with rights? Social movements, law and liberal imaginations. Pluto Press.